Robert's Paw's Boyhood - Continued!

Bear & Kris

Each day, while Bev is away playing bridge, I am rationing myself to just a few stories a day while reading "Robert’s Paw’s Boyhood.” The alligator in Paw’s “big trough” was a complete surprise to me and that is where I am now.

I love it so much that I often read individual stories twice or three times. I am working on mastering Paw’s depiction of southern Alabama lingo so I can read it off at normal conversational speed … with feeling. When you do that smoothly, you can imagine the characters better and, for example, recall how Paw’s black cook, Claudia, used to sound when we visited Montgomery.

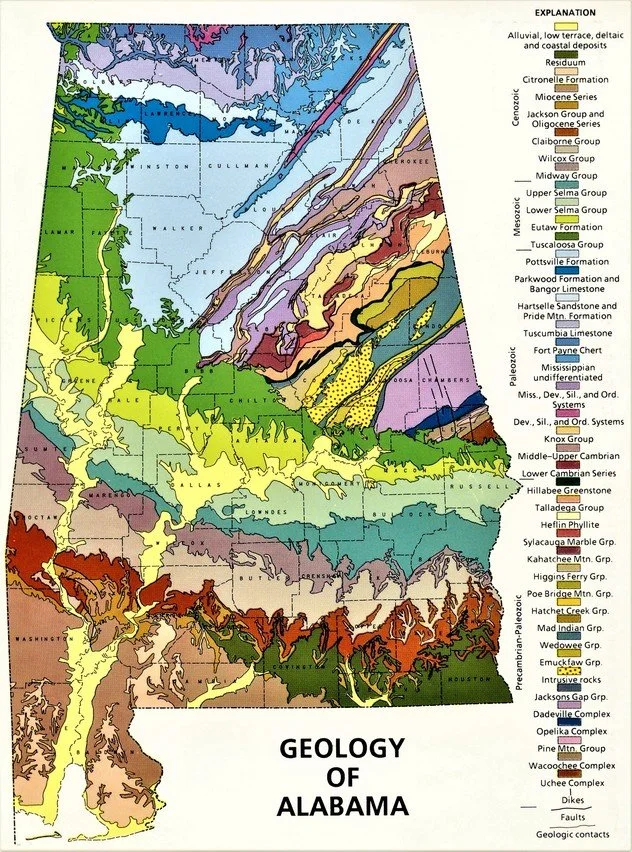

Exaggerated descriptions of events like having your horse up to his ears in “Alabama Black Mud” while crossing a low spot in your path is really good storytelling. Alabama Black Mud is a real, geologically defined thing and it forms a famously fertile “belt” right across Alabama where all the best cotton was grown.

I remember Uncle Mack proudly telling me that you could dig down as deep as you like in the Black Belt and still be in rich, fertile black soil. “You plant cotton just by walking along and poking a hole in the ground with your big toe, dropping in one seed, and stomping it with your heel.” He said, "One plant per step was the standard spacing.”

He insisted we all pick some cotton bolls from roadside plants. They looked white and fluffy and friendly, but spiny, rough and sharp they were. Everyone got poked and bled in a few places.

On several Spring Vacations to Alabama, we drove out into the “Black Belt” to see the sites on the plantation where much of Paw’s book's action happened. Most of the plantations were still vast cotton fields then. In just a few years cotton was to be replaced by cattle as the primary income producer in those counties, ending a two hundred year old tradition. That had already started.

Farmers bull-dosed large dirt dams, with a muddy road on top, that blocked streams and small valleys creating ponds or “Tanks” to provide water for their cattle. Any trees that had been in the little valley stood up out of the water, died and turned ghostly white in the sun. A very popular Alabama government program provided fish hatchery raised fingerlings for free if a new tank was built. Largemouth Bass the free fish were.

At the road approaching any tank which had become well known in the fishing community for its large crop of good sized Bass, the farmer would nail a tin can to the fencepost with holes poked into its bottom to drain rainwater out. Uncle Mack scooped all the coins in the car up and rattled them into the can. My father once asked, “why don’t you put in a dollar bill?” “Because the crows will pull it out to play with it,” Mack answered.

I can tell lots of stories of the mysterious, dark Cypress Swamp where we fished for Gar and Bass and Perch. The water was black. The cypress trees were ancient with great drooping garlands of soft, grey, peeling bark clinging to them. They were so thick and tall it was almost dark down at water level. Cypress Knees, growing wooden structures that indeed looked like knees poked up out of the water everywhere, some really short, some as tall as a man. They allowed the tree’s roots to breath, I learned.

Birds, frogs turtles and snakes loved the place. Bats could be spotted clinging upside down above us. Spanish Moss hung so thick you had to use an Oar to push it aside. Slithery and crawly things raced to get out of the way of the leaky row-boat.

That heavy row-boat was hand-crafted out of roughhewn cypress planks. It leaked and filled with rainwater and had to be bailed out continuously. It had no seaworthy characteristics. The bow was as square as the stern. All the seams were painted with black tar on the outside. However, there were generous seats running side to side, nailed in place, and these were often dry.

We always caught lots of Largemouth Bass, enough for a feast when we got back to Aunt Frances’ kitchen. The others we threw back in. Each year, we came back to adventure and fish in the cypress swamp. As a boy, nobody I knew had their own cypress swamp to tell about.

The land and the “Big House” were still owned by the Barnes family in the hands of Uncle Rawden (SP?). The great room of the Big House was filled with odd furniture and paintings and rugs. It was bright and cosy all at the same time. The falling down ruins of the row of slave quarters, a dozen or so little, individual cabins with stone chimneys and caved in roofs could still be seen when I was very young.

Near the big house was a small but very deep depression (a deep sink-hole really) at the bottom. It contained an ancient looking green-water pond populated with colorful Koy fish that were (according to locals) two hundred years old. We all believed them when we threw bread crusts into the water and attracted one of the bottom hugging monsters to break the surface.

Guys, many thanks again for all the skill and loving work on this project. It is such a treasure.

LoveYa! Dad